Sommaire :

Une inondation est une submersion temporaire par l’eau de terres qui ne sont pas submergées en temps normal.

une inondation peut avoir diverses origines et survenir :

A partir de cette approche très sommaire, une première typologie des inondations peut être dressée :

Quant aux inondations dues aux eaux pluviales des réseaux d’assainissement, leur inclusion ou non dans le phénomène général qualifié d’inondation dépend des auteurs, voire des réglementations.

Sur le plan opérationnel de la prévision des inondations et de la préparation à la gestion de crise, le ministère en charge de l’Environnement qualifie de crues soudaines les crues survenant sur des bassins versants dont le temps de réponse se situe entre 2 heures (délai en deçà duquel seuls des dispositifs locaux très spécifiques permettent une anticipation) et une demi-douzaine d’heures (délai au-delà duquel on entre dans le champ de la prévision des inondations classiques).

A ces inondations provoquées directement ou indirectement par des précipitations, doit être ajouté le cas de la submersion marine qui résulte de l’élévation, temporaire ou permanente, du niveau de la mer ; il est traité dans une fiche spécifique.

Le risque inondation est le premier risque naturel en France par le nombre de communes concernées (près de la moitié des communes, à des degrés divers, dont 300 agglomérations), l’étendue des zones inondables (5 % du territoire métropolitain, au vu du rapport sur l’évaluation préliminaire des risques d’inondation (EPRI) 2011 dont l’objectif est d’évaluer les risques potentiels d’inondations extrêmes, ce qui induit alors la transparence des ouvrages hydrauliques), les populations résidant dans ces zones (selon l’Observatoire des territoires, 9 % de la population en 2006 pour des évènement sensiblement centennaux ; selon l’EPRI 2011, 16,8 millions de résidents permanents en métropole et au moins 9 millions d’emplois), sa fréquence et l’importance des dommages qu’il provoque. De ce fait, ceux-ci sont multiples, qu’il s’agisse de victimes (morts, blessés) pour les catastrophes les plus graves et toujours de dégâts directs ou indirects ; c’est d’ailleurs le premier poste d’indemnisation au titre des catastrophes naturelles (55 % du total, devant la sécheresse 41 %).

Certains évènements météorologiques peuvent avoir des impacts particulièrement lourds ; à titre d’illustration, sont détaillés dans le rapport ci-après les dommages matériels causés par les innondations de décembre 2003 sur 24 départements du grand quart sud-est de la France ; outre le bilan humain (7 morts ; 27 000 évacuations), il convient d’ajouter à l’estimation initiale de 1, 092 milliard d’euros les coûts d’intervention, les incidences indirectes, etc.

Le risque d’inondation est directement lié aux précipitations : orages d’été qui provoquent des pluies violentes et localisées ; perturbations orageuses d’automne, notamment sur la façade méditerranéenne, mais dont les effets peuvent se faire ressentir dans toute la moitié sud du pays ; pluies océaniques qui occasionnent des inondations en hiver et au printemps, surtout dans le nord et l’ouest de la France ; fonte brutale des neiges au rôle parfois amplificateur, en particulier si des pluies prolongées et intenses interviennent alors. Les bassins versants, selon leur taille, peuvent y répondre par des inondations de divers types en fonction de l’intensité, de la durée et de la répartition de ces précipitations.

Le risque peut être amplifié selon la pente du bassin versant et sa couverture végétale qui accélèrent ou ralentissent les écoulements, selon les capacités d’absorption et d’infiltration des sols (ce qui par ailleurs alimente les nappes souterraines) et surtout selon l’action de l’homme qui modifie les conditions d’écoulement … ou s’installe sur des zones particulièrement vulnérables.

Des phénomènes particuliers, souvent difficilement prévisibles, peuvent aussi aggraver très fortement localement le niveau de risque, qu’ils soient naturels (débâcle glaciaire par exemple) ou anthropiques (rupture de digues, etc.).

En accompagnement à la mise à disposition, sur un site spécifique, de cartes des remontées de nappes par commune (voir § 3.1 ci-après), le Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (BRGM) présente de façon très complète le phénomène et ses causes, les principales conséquences en résultant pour les bâtiments et les infrastructures ainsi que les précautions à prendre dans les zones à priori sensibles ; il fournit également une typologie des inondations correspondantes et analyse le comportement des deux grands types d’aquifères que sont d’une part les nappes des formations sédimentaires et d’autre part les nappes contenues dans les fissures et fractures des roches dures du socle.

En accompagnement à la mise à disposition, sur un site spécifique, de cartes des remontées de nappes par commune (voir § 3.1 ci-après), le Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (BRGM) présente de façon très complète le phénomène et ses causes, les principales conséquences en résultant pour les bâtiments et les infrastructures ainsi que les précautions à prendre dans les zones à priori sensibles ; il fournit également une typologie des inondations correspondantes et analyse le comportement des deux grands types d’aquifères que sont d’une part les nappes des formations sédimentaires et d’autre part les nappes contenues dans les fissures et fractures des roches dures du socle.

Les cours d’eau de plaine sont soumis à des inondations lentes qui permettent généralement l’annonce des inondations et l’évacuation des personnes menacées. Néanmoins, la sécurité des personnes est parfois compromise, le plus souvent par non-respect des consignes ou par méconnaissance du risque, en particulier celui induit par la vitesse dans les zones dites d’écoulement (on estime par exemple que pour un enfant la limite de déplacement est de 50 cm d’eau ou une vitesse de courant inférieure à 50 cm/s).

Compte tenu des surfaces concernées, ces inondations ont souvent des conséquences économiques très lourdes, d’autant que les submersions peuvent se prolonger sur plusieurs jours, voire sur plusieurs semaines, entraînant des dégâts considérables aux biens, des perturbations importantes aux activités, des désordres sanitaires ainsi que des préjudices psychologiques parfois graves.

Compte tenu des surfaces concernées, ces inondations ont souvent des conséquences économiques très lourdes, d’autant que les submersions peuvent se prolonger sur plusieurs jours, voire sur plusieurs semaines, entraînant des dégâts considérables aux biens, des perturbations importantes aux activités, des désordres sanitaires ainsi que des préjudices psychologiques parfois graves.

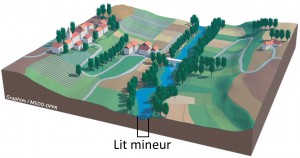

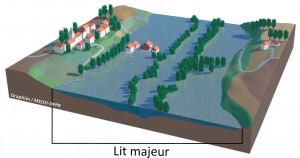

Lors d’une crue, tout cours d’eau peut abandonner son lit ordinaire (ou lit mineur) dont la capacité est généralement limitée à des débits de crue de période de retour de l’ordre de 1 à 5 ans pour occuper tout ou partie du lit majeur en fond de vallée qui constitue une zone dite d’expansion et contribue, par sa capacité de stockage des eaux, à un certain laminage des débits pour l’aval. Lors de leur retrait, les eaux les plus hautes laissent des traces, appelées laisses d’inondation : marques sur les murs, déchets accrochés aux branches, etc.

Lors d’une crue, tout cours d’eau peut abandonner son lit ordinaire (ou lit mineur) dont la capacité est généralement limitée à des débits de crue de période de retour de l’ordre de 1 à 5 ans pour occuper tout ou partie du lit majeur en fond de vallée qui constitue une zone dite d’expansion et contribue, par sa capacité de stockage des eaux, à un certain laminage des débits pour l’aval. Lors de leur retrait, les eaux les plus hautes laissent des traces, appelées laisses d’inondation : marques sur les murs, déchets accrochés aux branches, etc.

2.3 Crues torrentielles

Autant que la distinction fondée sur la dynamique de la crue (temps séparant les pluies et la montée des eaux), ce qui différencie les crues torrentielles des crues des rivières de plaine – qualifiées habituellement de crues « liquides » -, c’est la charge solide grossière qui accompagne les écoulements et aggrave significativement leur impact sur les personnes et les biens exposés.

Dès que la pente s’accentue, les écoulements deviennent de plus en plus chargés :

Types de cours d’eau, mécanismes de transport solide et types de crues / L. Besson et M. Meunier 1995

Si les matériaux fins transportés par suspension sont en général peu dommageables, il n’en est pas de même des sédiments véhiculés par charriage ou par coulées de laves torrentielles, qui peuvent aussi provoquer par engravement des exhaussements de lit puis des divagations ou obstruer le cours de la rivière émissaire aval ; par ailleurs, les écoulements ont une capacité érosive importante, à l’origine d’affouillements et de glissements de berges (voire de versants).

Enfin, le transport de bois et de débris divers par flottaison peut aggraver significativement les conséquences des crues torrentielles par obstruction des lits ou des ouvrages notamment de franchissement, avec alors divagation vers des zones inhabituelles ; les barrages constitués par l’accumulation de matériaux flottants (embâcles) sont toujours susceptibles de se rompre et de provoquer à l’aval des débâcles dévastatrices, difficilement prévisibles.

Torrent du Manival dans la vallée du Grésivaudan (versant Est du massif de la Chartreuse) © S. Gominet

Les torrents se situent en tête de bassin versant, là où les pentes sont les plus fortes (> 6 %) : avec des débits très irréguliers, souvent intermittents, la réaction d’un torrent aux précipitations varie selon l’intensité, la durée et la chronologie de celles-ci, la nature géologique et la sensibilité à l’érosion des terrains traversés, l’état de la couverture végétale ou forestière du bassin de réception. Les matériaux transportés s’accumulent sur le cône de déjection du fait d’une brusque réduction de la pente, la totalité de celui-ci pouvant être, en l’absence d’aménagement, balayée au gré des apports successifs des crues.

A l’aval immédiat, les rivières torrentielles constituent une catégorie de cours d’eau intermédiaire entre les torrents et les rivières ; de pentes plus faibles que les torrents (quelques %), elles peuvent encore être le siège d’écoulements hyper-concentrés ; on peut y observer crues rapides et débordements soudains, affouillements intenses et/ou apports solides dans le lit mineur comme dans le lit majeur – ces phénomènes opposés pouvant se succéder sur un même tronçon, au cours d’une même crue, et entraîner des divagations du lit mineur dans tout le lit majeur -, création d’embâcles notamment au droit d’ouvrages insuffisamment dimensionnés ou mal conçus.

A noter le cas particulier des rivières torrentielles pour leur tronçon amont et des torrents lorsque leurs bassins versants sont partiellement de type glaciaire : ces cours d’eau peuvent être soumis à de brusques variations de débit et de transport solide selon les aléas propres à la vie des glaciers (voir fiche RN 5 : Neige, avalanches et risques glaciaires).

Le guide publié récemment par le ministère en charge de l’Environnement dans la collection Construire en montagne (voir § 3.6 ci-après), en particulier ses chapitres 1 et 2, explicite d’avantage les phénomènes liés aux crues torrentielles et leurs différences avec les crues des zones de plaine ; il les illustre par de nombreux exemples, souvent de catastrophes.

Le ruissellement est un phénomène d’écoulement non organisé de l’eau sur un bassin versant suite à des chutes de pluies ou à une fonte brutale du manteau neigeux. Il perdure jusqu’au moment où il rencontre une rivière, un réseau d’assainissement ou un marais. D’origine naturelle ou/et anthropique, il est souvent accompagné de phénomènes érosifs soit généralisés soit plus concentrés (par exemple sous forme de coulées boueuses).

Une fiche du Mémento lui est consacrée compte tenu de l’importance de ce risque et des possibilités d’action au niveau local.

L’impact du changement climatique doit être évalué pour les 2 volets constitutifs des crues : le volet élément liquide d’une part, le volet transport solide d’autre part.

En ce qui concerne les inondations récentes, la plupart des experts considèrent que le caractère exceptionnel qui leur est trop souvent attribué résulte en fait d’une méconnaissance des crues historiques et d’une sous-estimation des débits de pointe pris en compte (compte tenu par exemple de séries hydrologiques, lorsqu’elles existent, ou météorologiques retenues trop courtes). L’accroissement des dommages résulte essentiellement de l’accroissement considérable de la vulnérabilité au cours des dernières décennies, l’impact éventuel du changement climatique ne pouvant généralement se distinguer de l’intervalle de confiance ou de la marge d’incertitude qui devrait accompagner toute détermination d’un débit de crue.

Les observations menées suite à certaines crues de torrents dont les bassins versants concernent pour partie la haute altitude, notamment en Suisse et dans les Alpes du Nord, laissent supposer la mobilisation de nouvelles sources de matériaux venues grossir le transport solide, du fait par exemple de la disparition locale de névés ou d’un début de dégel du pergélisol (sol restant gelé en permanence, la couche superficielle pouvant toutefois dégeler l’été pour regeler ensuite pendant la période froide).

La difficulté de faire des prévisions pour l’avenir tient notamment à ce que les réponses d’un cours d’eau à des épisodes pluvieux identiques peuvent être très différentes si les conditions initiales diffèrent : nature géologique des terrains, état de surface des versants, état de la couverture végétale, état de saturation initiale des sols, importance de la couverture neigeuse, facteurs anthropiques (dont en particulier les modes d’occupation de l’espace) également.

Par contre, il est plus facile d’imaginer que les volumes mobilisables sous forme surtout de laves torrentielles, voire de charriage, par les torrents dont les bassins versants se situent pour partie en altitude, seront très vraisemblablement accrus par la mise à disposition de matériaux de type morainique, éboulis de pente, voire issus d’éventuelles déstabilisations de versants du fait d’un dégel superficiel ou d’une fonte du pergélisol ainsi que, selon la sensibilité des sols, d’un recul des glaciers.

La gouvernance de l’eau a d’abord porté essentiellement sur la résolution des conflits relatifs à l’usage de l’eau et donc à sa bonne et juste répartition ou à son libre écoulement ; d’autres intérêts se sont progressivement greffés tels la valeur piscicole des eaux, la protection des populations contre les inondations par de grands travaux, etc.

La politique de l’eau est ainsi devenue une politique globale, rassemblant de nombreux objectifs dans le but d’assurer une gestion équilibrée et durable de la ressource (article L.211-1 du Code de l’environnement) ; pour cela, une structuration de la gouvernance s’est mise en place notamment au niveau des bassins (avec les agences de l’eau , les schémas directeurs d’aménagement et de gestion des eaux (SDAGE), etc.) et des sous-bassins hydrographiques (avec les schéma d’aménagement et de gestion des eaux (SAGE), etc.) afin d’associer aux décisions les multiples acteurs potentiels et coordonner leurs actions. C’est dans ce cadre général, de plus en plus défini au niveau européen, que s’inscrit la politique de prévention des inondations.

La prévention des inondations est, comme pour la plupart des risques, à base évènementielle et s’est essentiellement construite sur les retours d’expérience de catastrophes successives, relativement nombreuses au cours des dernières décennies.

Aujourd’hui, la mise en œuvre de la directive européenne de 2007 relative à l’évaluation et à la gestion des risques d’inondation est en cours avec pour échéance finale 2015 (articles L.566-1 / 13 du Code de l’environnement) ; par ailleurs, mis au point après une large concertation suite à la tempête Xynthia du 28/02/2010 (53 morts) et aux inondations du Var du 15/06/2010 (26 morts et disparus), le plan submersion rapide (PSR) a retenu 4 axes prioritaires d’intervention, à savoir : maîtriser l’urbanisation dans les zones à risques ; améliorer les systèmes de surveillance, de prévision et d’alerte ; renforcer la fiabilité des digues ; développer enfin une véritable culture du risque (à travers notamment les plans communaux de sauvegarde (PCS)).

La documentation sur les évènements passés, y compris les inondations à caractère historique, était relativement dispersée et de ce fait parfois ignorée, sauf cas particuliers (comme par exemple, en matière d’inondations, dans certains bassins de grands fleuves où la préoccupation est ancienne ou, en matière de crues torrentielles, dans les 11 départements alpins et pyrénéens pourvus d’un service (inter)départemental de Restauration des terrains en montagne (RTM)). Aussi, dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre de la Directive inondations, l’Institut national de recherche en sciences et technologies pour l’environnement et l’agriculture (Irstea, ex Cemagref) a été chargé d’élaborer un guide méthodologique sur la collecte des données historiques et de mettre au point une base de données spécifique sur les inondations passées.

Par ailleurs, pour la France métropolitaine, Météo France met à disposition sur un site spécifique les cartes (jusqu’au niveau départemental) des épisodes pluvieux les plus intenses répertoriés depuis 1958, avec les statistiques correspondantes, ainsi que le relevé de nombreux évènements marquants antérieurs. Pour sa part, la Caisse centrale de réassurance (CCR) présente pour les inondations les plus significatives une description synthétique de l’évènement et une carte des communes impactées avec les fourchettes de coût correspondant aux indemnisations versées.

Une vue prospective du risque d’inondation a été établie pour les phénomènes d’inondations susceptibles de se produire par remontée de nappes ou par débordement de cours d’eau.

Les atlas des zones inondables (AZI) sont des documents de connaissance qui ont pour objet de rappeler l’existence et les conséquences des inondations historiques ainsi que de présenter les caractéristiques des aléas pour la crue la plus forte retenue (crue centennale ou crue historique) ; la délimitation de ces zones inondables s’appuie sur la méthode dite « hydrogéomorphologique » qui étudie le fonctionnement naturel des cours d’eau en analysant la structure des vallées ; les espaces ainsi identifiés sont potentiellement inondables, en l’état naturel du cours d’eau, avec des intensités plus ou moins importantes suivant le type de zone décrite.

Les atlas des zones inondables, accessibles pour certains sur le site Cartorisque et pour la quasi totalité sur les sites des directions régionales de l’environnement, de l’aménagement et du logement (DREAL) ou des préfectures (direction départementale des territoires (et de la mer) (DDT(M)) avaient vocation à être enrichis à mesure de l’évolution des connaissances. Ils constituent, à défaut de cartographies plus élaborées, un outil de référence pour les services de l’Etat et pour les collectivités dans les différentes tâches dont ils ont la responsabilité (porter à connaissance, application du droit des sols, etc.).

Plusieurs bulletins de vigilance concernant les inondations sont émis à l’attention des préfectures, des services, des élus et du grand public dans un objectif de protection civile :

Ces différentes cartes sont actualisées au moins 2 fois par jour avec, lorsqu’un département est classé en orange ou en rouge, une procédure de suivi spécifique et la diffusion d’un bulletin de vigilance décrivant le phénomène et prodiguant, au vu de ses conséquences prévisibles, les conseils de comportement appropriés.

C’est à partir du niveau orange qu’est mis en œuvre par le préfet de zone ou de département un dispositif d’alerte destiné aux maires, aux Conseils généraux et aux services opérationnels.

Cette prévision est mal adaptée à la mise en place d’une prévention couvrant les crues des petits bassins versants : en effet, la vigilance crues ne concerne qu’environ 20 000 km de cours d’eau, soit seulement une partie des cours d’eau présentant des risques d’inondations et de crues ( le chevelu total s’étendant sur un linéaire de l’ordre de 500 000 km) ; en l’absence d’un tel dispositif, la capacité à anticiper une gestion de crise est incertaine, l’utilisation de la carte de vigilance météorologique étant souvent d’interprétation délicate, voire même inadaptée pour les crues soudaines. C’est pourquoi un certain nombre de collectivités ont mis en place une prévision locale du risque, souvent avec l’appui de prestataires extérieurs (gestionnaires du réseau d’assainissement, etc.) : cette prévision s’appuie notamment sur l’exploitation de données en provenance de stations de mesure complémentaires (précipitations, débits) et d’images radar en temps réel.

Aussi, le récent PSR prévoit un renforcement des outils de surveillance, de prévision et d’alerte par :

Aux actions générales menées par l’Etat sur une base identique avec les adaptations nécessaires à la nature du risque, s’ajoutent celles très nombreuses d’organismes notamment de bassin, d’associations à caractère national ou local. Parmi celles-ci, le Centre européen de prévention du risque d’inondation (CEPRI) a mis en place un réseau d’échanges et de capitalisation des savoir-faire à l’attention des collectivités et conduit ou participe à la réalisation d’études méthodologiques et techniques sur la vulnérabilité des personnes et des biens face au risque d’inondations (lentes) au niveau d’un territoire.

Aux actions générales menées par l’Etat sur une base identique avec les adaptations nécessaires à la nature du risque, s’ajoutent celles très nombreuses d’organismes notamment de bassin, d’associations à caractère national ou local. Parmi celles-ci, le Centre européen de prévention du risque d’inondation (CEPRI) a mis en place un réseau d’échanges et de capitalisation des savoir-faire à l’attention des collectivités et conduit ou participe à la réalisation d’études méthodologiques et techniques sur la vulnérabilité des personnes et des biens face au risque d’inondations (lentes) au niveau d’un territoire.

Par ailleurs, la présence de repères de crues contribue localement à la sensibilisation et à l’entretien de la mémoire collective : le maire, avec l’appui des services de l’Etat, doit en effet dans les parties de sa commune exposées au risque d’inondation procéder à l’inventaire des repères de crues existants, compléter, si nécessaire, ce réseau pour tenir compte des crues historiques et enfin établir de nouveaux repères suite à toute nouvelle crue exceptionnelle.

Deux approches différentes sont nécessaires selon que l’on ait affaire à un aléa de type inondation lente ou à un aléa de type divagation et affouillement/alluvionnement.

Dans le premier cas, les caractéristiques hydrauliques peuvent être décrites à partir de deux ou trois paramètres : la hauteur, la vitesse et, le cas échéant, la durée de submersion. L’expert a largement recours aux modélisations s’appuyant sur les lois de l’hydraulique fluviale (qui ne tient pas compte ou très peu de la concentration de l’écoulement lors d’une crue).

Dans le second cas, la charge solide ne peut plus être négligée compte tenu des interactions fortes entre la phase liquide, la phase solide et la géométrie du lit. Les spécificités à prendre en compte sont nombreuses et tant les variabilités des phénomènes que les niveaux d’incertitude sont beaucoup plus élevés que précédemment. Aussi, l’expert aura-t-il une approche plus naturaliste et multicritères : il s’efforcera, en fonction notamment de l’historique, de l’analyse du site et de sa prédisposition au risque ainsi que, le cas échéant, des résultats de diverses modélisations, d’apprécier à la fois les niveaux d’intensité prévisible (hauteur d’écoulement, taille et concentration des sédiments, affouillements, flottants, laves torrentielles) et les probabilités d’atteinte.

Les différents guides méthodologiques spécialisés sur les plans de prévention des risques d’inondation (PPRI) permettent de comprendre comment, selon sa nature, cartographier l’aléa et le prendre en compte lors de l’élaboration d’un PPR ; les mêmes principes peuvent être mis en œuvre pour réaliser un plan local d’urbanisme (PLU) par intégration directe de l’aléa ou pour instruire un dossier d’urbanisme en l’absence de tout document réglementaire ou en cas de connaissance de données nouvelles (évènements, expertises).

Compte tenu que le guide PPR sur les crues torrentielles n’est pas à ce jour publié, il est recommandé de se reporter sur ce thème aux chapitres 3, 6 et 7 du guide Construire (voir § 3.5 ci-après).

La réduction de la vulnérabilité de l’existant (bâtiments, réseaux, maintien de l’activité) et la bonne réhabilitation des quartiers endommagés suite à une inondation représentent des enjeux très importants au niveau national.

La réduction de la vulnérabilité de l’existant (bâtiments, réseaux, maintien de l’activité) et la bonne réhabilitation des quartiers endommagés suite à une inondation représentent des enjeux très importants au niveau national.

Pour tout projet en zone de risque acceptable, les constructeurs auraient intérêt à prendre connaissance de différents guides existants dont en particulier ceux publiés par le ministère en charge de l’Environnement et par le CEPRI ; ils pourront aussi utilement compléter leur documentation, en matière notamment de dimensionnement de structures, par la lecture du cahier de recommandations mis à disposition des constructeurs, des assurés et aussi des autorités (suisses) par l’Association des établissements cantonaux d’assurance incendie suisses (VKF/AEAI) pour leur permettre de se prémunir individuellement, qu’il s’agisse de bâtiments existants ou à réaliser.

Les dispositifs de protection s’inscrivent dans des politiques plus globales, menées au niveau d’unités de gestion homogène, telles celles définies dans les programmes multiobjectifs de type grands fleuves et contrats de rivière, dans les programmes spécialisés inondation de type Programme d’actions de prévention des inondations (PAPI) ou PSR ou dans les programmes RTM.

Les mesures doivent être différenciées selon les types d’inondation, compte tenu par exemple de la nature ou des délais de prédictibilité du phénomène ; les réglementations sont souvent complexes et les financements variés (Etat, collectivités territoriales, agences de l’eau, etc.).

Par ailleurs, au vu de l’évolution des connaissances ou de la réglementation, de l’expérience acquise, etc., la remise en cause de l’efficacité d’un dispositif de protection ne peut jamais être exclue.

La stratégie de protection repose sur des mesures qui peuvent être complémentaires associant par exemple défense temporaire et défense permanente ou génie civil et génie biologique :

Pour rester opérationnel, tout dispositif de défense permanente doit faire l’objet d’une surveillance régulière attentive et ensuite, si nécessaire, des entretiens préconisés. L’état du lit et des berges des ruisseaux, des torrents, des fossés, des drains, etc. doit faire l’objet d’une vigilance particulière.

Pour rester opérationnel, tout dispositif de défense permanente doit faire l’objet d’une surveillance régulière attentive et ensuite, si nécessaire, des entretiens préconisés. L’état du lit et des berges des ruisseaux, des torrents, des fossés, des drains, etc. doit faire l’objet d’une vigilance particulière.

Seuls à ce jour les ouvrages construits en vue de prévenir les inondations et les submersions font l’objet d’une réglementation spécifique, fonction de leur dangerosité potentielle estimée au vu de leurs caractéristiques (par exemple, pour les digues hauteur et population protégée – voir divers renvois ci-après) ; la loi précise à leur sujet que la responsabilité du gestionnaire ne peut être engagée à raison des dommages que l’ouvrage n’a pas permis de prévenir dès lors qu’il a été conçu, exploité et entretenu dans les règles de l’art et conformément aux obligations légales et réglementaires (article L. 568-8-1 du Code de l’environnement).

La nature et la diversité des situations auxquelles sont confrontés pouvoirs publics, acteurs locaux et population peuvent être appréhendées à partir des retours d’expérience tirés d’évènements passés : lorsqu’il s’agit de catastrophes de grande ampleur, ceux-ci sont conduits à la demande de l’Etat par des missions d’inspection spécialisées (voir les différents rapports en annexe) ; pour des évènements plus limités, ils sont menés, le cas échéant, sur initiative locale. Une des actions menées dans le cadre du projet européen Interreg III A Alcotra PRINAT « Création du Pôle des risques naturels en montagne » (2003-2007) a consisté à confronter les points de vue de différents acteurs (collectivités, services, associations, etc.) ayant participé à des gestions de crise du fait de crues torrentielles ; à ce titre, elle offre divers enseignements et pistes de réflexion.

En ce qui concerne les communes susceptibles d’avoir à gérer une situation de crise, il ne peut être que recommandé aux maires concernés d’établir et de faire vivre un PCS, que celui-ci soit obligatoire ou non : en effet, la gestion de crise se prépare hors période de crise, au travers notamment d’exercices de simulation, afin d’être apte à répondre le moment venu à tous les aspects d’un tel épisode et dans toutes ses phases.

En outre, une attention particulière attachée à l’état d’entretien des cours d’eau et autres axes d’écoulement des eaux, l’établissement de relations périodiques avec les gestionnaires des ouvrages de protection concernant la commune (par exemple : digues, ouvrages RTM), la participation à la mise en place, si nécessaire, d’une prévision locale du risque, etc., l’exercice effectif de ses pouvoirs de police enfin, sont autant d’atouts pour un maire soucieux de limiter les conséquences d’une éventuelle inondation.

Inondations Extrait du MENTO du Maire Dernière mise à jour : 27 juin 2012

Jean-Pierre Requillart